The Family Centre’s study of Samoan attitude to health stated: “Samoan people believe that the person is ‘itu lua’, that is the person has physical, mental and spiritual aspects. We view ourselves as whole beings. In other words the spirit, the body, the will… It was emphasized that the Samoan self is seen as a total being comprising spiritual, mental and physical elements which cannot be separated. If I become mentally unwell, everything else is not well. If I become physically unwell, everything else is not well. I cannot say, ‘I will leave my spirituality while I go and get on with my physical function’, or ‘I will put aside my mental function while I undertake my spiritual duty’. The whole person is all parts. The person cannot be divided by anyone.” (Tamasese, Peteru, Waldegrave, & Bush, 2005)

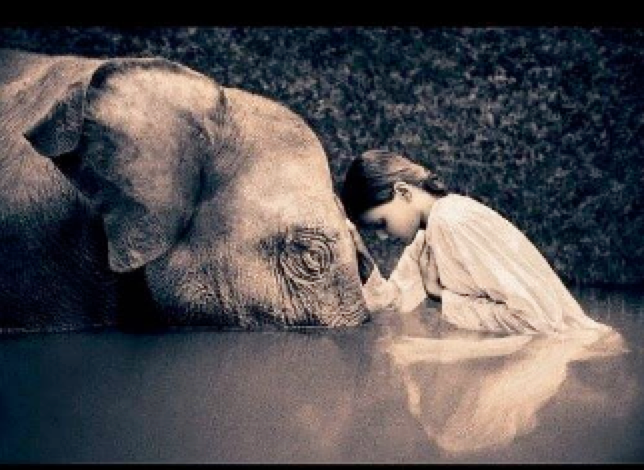

I have been taught to understand the position of human beings within nature by the Kaska First Nations of Canada’s Yukon. For the Kaska, health has a lot to do with respecting A’i , (pronounced “ah ee” as with a bar above the i). I gather they see all existing things to be governed by a law or laws which define relationships between things, and A’i is that law.

When we abide by A’i, we don’t get it wrong in terms of our relations with people and with all living things including animals, the plants, everything in the universe. How you speak to each other, who you speak to and how you speak. How you kill the animals and how you take care of the remains of the animals you kill. Everything from the moment you get up to the moment you go to bed, are guided by A’i. A’i guides not only the present, but the future, and the past is always kept in mind, in terms of ancestors. In traditional times, there were sanctions when people did not abide by A’i. In extreme cases people were exiled, such as a death. Many times people would pay if they were somehow responsible for a death, even in a minor way, there had to be payment made to the family and perhaps even the whole community.

The phrase we have come up with in modern times meaning respect is “dene a’i nezen”, or “dene a nezen”… the a being short for A’i. Because we don’t have a word for respect, the phrase means… you are abiding by it, or directly translates to “people liking, or loving A’i .” (McDonald, 2010)

This is similar to the Samoan “Tealo va fealoai”, which means “The space between people is sacred.” (Tamasese, Peteru, Waldegrave, & Bush, 2005) Va, for Samoans, is the space between two people who are facing each other, and it can be sacred: “care needs to be taken in relating to each other”. (Tamasese T. K., 2010)

A colleague, Wahiri Campbell, is a respected Maori elder who wrote that “sacred”, (“tapoo” in his language) means a thing must be protected and that it is forbidden. He said, for example: “If a person drowned in these waters, no fish may be taken here for three months.” Another example is that the sexuality of a child is “tapoo” (sacred). It must not be touched and it must be protected. (Campbell, 1994)

Bust those rules and your health is in trouble. So is any chance of being a force for healing.

– McDonald, L. (2010, February 13). (R. Routledge, Interviewer)

– Tamasese, K., Peteru, C., Waldegrave, C., & Bush, A. (2005). Ole Taeao Afua, the new morning: a qualitative investigation into Samoan perspectives on mental health and culturally appropriate services. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , 300-309.

– Tamasese, T. K. (2010, April 11). (R. Routledge, Interviewer)